In 1978, Terrence Malick was regarded as one of the most promising newcomers in Hollywood. His sophomore movie Days of Heaven was a pure masterpiece following his exceptional 1973 first album Badlands . Malick had endless possibilities for his next project. However, as the Hollywood legend suggests, he vanished instead.

After a two-decade absence, Malick astonishingly came back to the cinematic world with his third movie. The Thin Red Line Today, this mysterious director has become highly productive. From 2011 to 2019, they produced six movies. This marks quite a shift from the long gap between their second and third releases.

Despite the higher productivity, Malick remains an enigma. His last known interview was with the French newspaper Le Monde back in 1979. Since then, he hasn’t provided any direct quotes to journalists, and the sole photograph permitted for public release is a blurry image of him at work directing. The Thin Red Line .

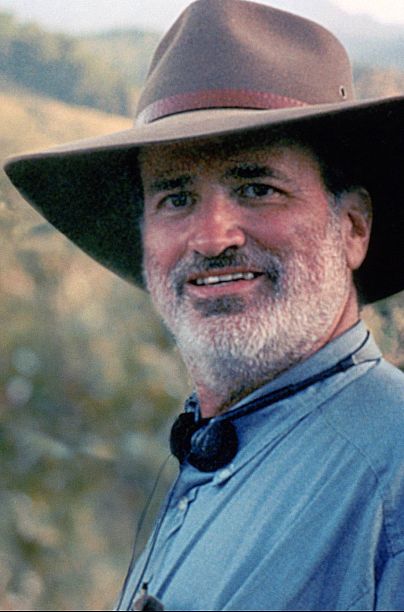

The scene is enveloped in the warm glow of late afternoon. That magical time. His father, Emil Malick, captured this moment. Despite their disagreements, Terry continued to perceive himself through his dad’s perspective," states the biography accompanying the image. Appearing midway through the book, it encapsulates part of John Bleasdale’s significant challenge—shedding light on both Malick’s human side and his distinctive style within the realm of cinema.

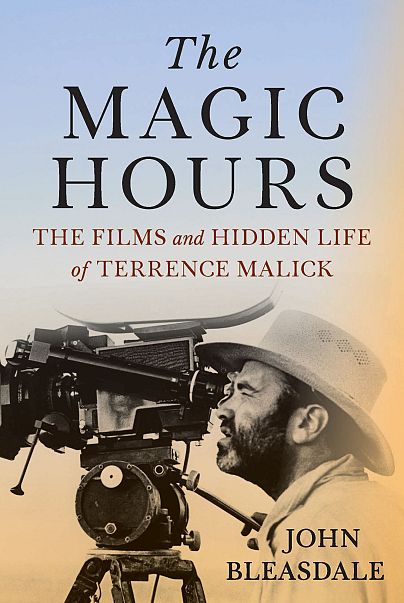

"The Magic Hours: The Films and Hidden Life of Terrence Malick" offers an extensive look at the filmmaker's journey, showcasing thorough investigative work through detailed insights into managing large teams both in front of and behind the lens. Bleasdale enriches this narrative with excerpts from newspapers, statements from colleagues, along with his individual reflections on Malick’s body of work.

This marks the first time Malick has been the subject of a biography. As expected, there is curiosity about whether Bleasdale managed to interview Malick directly. Although he mentions discussions with longstanding associates like production designer Jack Fisk and actors including Sean Penn, he dismisses the idea of having met with Malick personally, stating instead that they exchanged "very courteous emails."

However, "The Magic Hours" explores more aspects of Malick’s private life than any previous individual piece of writing. Is some of this data directly sourced from Malick himself, despite him not explicitly requesting attribution for these quotes? The most definitive response I receive from Bleasdale is, "If they were, I wouldn’t be able to reveal them."

While the detailed biography of Malick’s career is fascinating—especially the part about his challenging period during what has been termed his "wilderness years" and how his difficult times with producers Bobby Geisler and John Roberdeau fueled his creativity—it remains just one aspect. Knight of Cups - The most compelling parts of the book delve into how Malick’s personal life intertwined with his professional journey.

Bleasdale’s biography portrays Malick as an affable and highly approachable individual, equally likely to engage in lighthearted banter as they are to delve into profound philosophical discussions. Despite acknowledging Malick’s inclination towards introversion, it becomes evident that these descriptions should be used to dispel the myths perpetuating his image as a recluse within Hollywood circles.

As these legends are dispelled, details regarding Malick’s domestic life emerge. His strained connection with his father, the absence of his siblings, and his romantic entanglements all influence Bleasdale’s interpretations of his movies and how they correlate with their respective release times.

"He observes that tragic brothers and troubled fathers recur throughout his films." However, even though aspects of his marriage to Michèle Monette shed some light on these themes, To The Wonder Bleasdale makes it evident that his body of work is not merely concealed autobiography.

I believe he strongly wishes to conceal aspects of his personal life," states Bleasdale. Similar to how his philosophical background and religious convictions frequently act as starting points for interpreting Malick’s work, Bleasdale argues this approach may be misleading. "He likely believes that reducing everything to those elements would prevent people from truly engaging with his films and finding their own meanings within them.

If Malick deliberately avoids public attention akin to a Barthes-like 'Death of the Author' approach to prevent his personal life from dominating viewers' interpretations of his work, wouldn't a biography contradict his artistic intentions? Bleasdale suggests this might be a misinterpretation of Malick's distancing himself from media exposure.

Bleasdale states, "He will definitely not pick up this book." According to him, "He has previously mentioned that he wouldn’t attend therapy as it would drain his energy. Instead of sharing insights through interviews, he prefers exploring within himself via his films."

Similar to his AFI classmate David Lynch’s well-known reluctance to explain the meanings behind his movies, Malick’s primary focus regarding his public persona is solely on his films themselves.

Engaging with these films, be it through a subsequent discussion or even reading a biography, allows them to become part of our lives. "Ultimately, the purpose of any film-related book should be to encourage readers to revisit the movies and appreciate them in a more profound and nuanced way," explains Bleasdale.

"The Magic Hours" lives up to this expectation. It fully immerses itself in how Malick integrates his personal story into a filmmaking approach that pushes the boundaries of the medium. The fact that it achieves this with his most controversial works is even more remarkable compared to what he does with his well-loved films. As Bleasdale outlines in his section on this topic, To The Wonder There is much more to his approach to filmmaking than just the apparent link between his narratives and his second wife.

It's peculiar. The film is ostensibly autobiographical but it's entirely narrated through Marina’s [played by Olga Kurylenko] perspective. Ben Affleck only has around three lines throughout the entire movie. It primarily focuses on her character and Javier Bardem playing a roving priest." According to Bleasdale, Malick remains creatively innovative even when delving into personal storytelling. "An autobiography doesn’t always mean laying out one's innermost reflections; instead, it can involve attempting to understand various viewpoints encountered over one's lifetime. This approach is quite magnanimous.

If Malick’s initial trio of films were regarded as masterpieces and his fifth – which was equally autobiographical – The Tree of Life cemented his return with the Palme d’Or at Cannes and Oscar nominations, his latter films have been largely criticised as meandering bores filled with droning spirituality and perfume-advert filmography.

Bleasdale contends that despite being highly abstract, his work retains an avant-garde artistic essence which continues to significantly impact cinema much like his previous productions.

Out of Malick's seven movies produced in this century, five were shot by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (known as Chivo). Their collaboration has shaped a distinctive visual style that characterizes their work together.

Over Chivo's debut collaboration with Malick on his first film, The New World , they developed a "dogma" for filming that involved utilizing "natural available light," strictly prohibiting underexposure, along with other guidelines that disallowed zooms and advised against pans and tilts in favor of movements "along the z-axis." This set of rules has become characteristic of Malick's films—sometimes even bordering on caricature—but these principles have also seeped into mainstream modern cinematography. Lubezki received his third Academy Award for his contribution to this work. The Revenant , a movie featuring distinct bear claw marks inspired by Malick’s work.

Bleasdale mentions films and directors whom he believes clearly show Malick's influence, with Paul Thomas Anderson being one of them. There Will Be Blood and The Master owe a significant debt to Malick’s period pieces. From last year’s Oppenheimer ", "You won't find that level of editing with two scenes split throughout the entire film; instead, most of the narrative relies on individual shots rather than complete scenes, excluding 'The Tree of Life' from consideration." Even this year’s Best Picture nominee. Nickel Boys is “totally The Tree of Life in its technique of montage and use of subjective camera work.

If his creations prove too challenging for typical viewers, it's because they push boundaries by experimenting with cinematic storytelling techniques, according to Bleasdale. The ultimate aim remains engaging audiences through narratives that forge fresh connections.

As someone not previously swayed by Malick’s work, Bleasdale presents a compelling human case for appreciating Malick both as a director and an individual. The author finds him more relatable when stripped of the enigmatic aura cultivated by media coverage.

As he cites one of Malick’s coworkers: "We truly thought each morning at work that our aim was to revolutionize the cinematic language."

"Terrence Malick: His Hidden Life and Filmography" by John Bleasdale is out now.